INSTITUTE FOR NATURAL RESOURCES

INSTITUTE FOR NATURAL RESOURCESYou are here

Ecosystem Services

- Intro

- Planning Resources

- Research Projects

- Articles & Stories

- Maps & Tools

- Reports & Publications

- Data

- Photos & Videos

- More

Multiple Facets of Ecosystem Services

Using an ecosystem services framework allows for the quantification or evaluation of those components of nature that can be readily linked to individual and societal well-being. The goal of the framework is to match changes in biological functions with changes in well-being so that the implications of wetland conversion or degradation are obvious and measurable. Because ecosystem services are a relatively new concept, many issues that are associated with defining and measuring ecosystem services still need to be resolved.

Distinguishing between Intermediate and Endpoint Ecosystem Services

It is challenging to define ecosystem services in such a way that a manageable number of services can be quantified and evaluated. By focusing on endpoint services, the biological functions of wetlands become more meaningful to the public and to those involved in wetland crediting and trading for wetland mitigation. For example, improved water quality can be considered an intermediate wetland ecosystem service (or an ecological function), while improved drinking water can be considered an endpoint service or outcome that matters most to people. As an example of the importance of distinguishing between endpoint and intermediate services, consider a stated preference survey (a method for valuing ecosystem services) that asks an individual's willingness to pay for improvements to an ecosystem service. It is likely that they would be willing to pay more for improvements to drinking water (an endpoint service) than improvements to water quality because they better understand the implications to their own well-being. This focus on endpoint services is also important for designing non-monetary geographic indicators , that ask questions such as, "Where can we restore wetlands that will maximize improvements to drinking water (an endpoint service)".

The table below shows the many terms used for describing the ecology (organization and operation) and the economics (human-centered outcomes) of wetlands. The term, "ecosystem services" is often used to describe both intermediate, ecological operations and economic outcomes.

Adapted from Fisher, Turner and Morling (2009)

‘Service Areas’ (Context and Direction) of Ecosystem Services

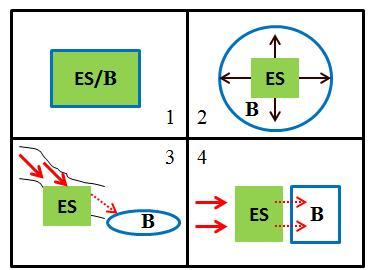

Ecosystem services are inherently defined by the benefits provided to individuals and society. Therefore, it is important to evaluate wetlands in the context of local land use/land cover configurations, human activities, and populations and demographics. The direction of a service is important for defining where and who are the primary beneficiaries of that service. The figure below describes the differences between where an ecosystem service is provided (ES-green) and where local populations benefit from that service (B-blue).

- On-site (Box 1): the services are provided and the benefits are realized in the same location (e.g., hunting and fishing).

- Multi-directional (Box 2): the services are provided in one location, but benefit the surrounding landscape without directional bias (e.g., aesthetics).

-

Directional (Boxes 3 and 4): the services benefit a specific location due to the flow direction: as downstream flood damage prevention (3) or coastal storm surge attenuation (4).

Adapted from Fisher, Turner and Morling (2009)

Classification of Ecosystem Services

It is often difficult to establish the link between ecological structure and function, such as "how do differences in soil and vegetation affect the ability of a wetland to filter excess nutrients and improve water quality?" Even more difficult is establishing the link between ecological functions and ecosystem services. The initial approach to establishing these linkages, is to first define a list of ecosystem services and then to group them by functional characteristics. To date, there is no universal or even nationally consistent classification of services; nor is there complete list of all services that can be generated by a specific ecosystem such as a wetland.

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment provides one way of grouping services into four basic categories based on their functional characteristics. While providing a useful (and popular) framework for ecosystem services, this classification is deficient in many ways such as ignoring the endpoint problem (discussed above), issues concerning biodiversity and the lack of clear linkages to field-based measurements that can be used to assess changes in ecosystem services. See the table: Ecosystem Service Classification for a list of wetland ecosystem services and links to the Millennium Assessment groups.

-

Provisioning Services: ecosystems supply a large variety of goods and other services for human consumption, ranging from food, water and raw materials to energy resources and genetic material.

-

Regulating Services: functioning ecosystems assure that essential ecosystem processes continue to operate in predictable ways. These are things like flood control, weather control, and sediment capture.

- Cultural Services:ecosystems provide an essential "reference function" and contribute to the maintenance of human health and well-being by providing spiritual fulfillment, historical integrity, recreation, and aesthetics.

- Supporting Services: ecosystems also provide a range of services that are necessary for the production of the three preceding service categories. These include nutrient cycling, soil formation, and soil retention.

Scales of Ecosystem Services

Ecosystem services are supplied to people at a range of spatial and temporal scales, varying from short-term and local (e.g. recreation at a neighborhood natural area) to long-term and global (e.g. carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation). Many of these broad-scale (long-term and global) services are not easily perceived by individuals and therefore, the aggregate of values derived from individuals will be less than the total value to society. For example, in a stated preference valuation survey, willingness to pay for maintaining or improving a neighborhood service will likely be higher than willingness to pay for a global regulating service such as carbon storage.

Adapted from Mitsch and Gosselink (2000).

The Marginal Value Paradox of Ecosystem Services

For most manufactured goods or services, if the availability of a product decreases or the demand increases then the marginal value (value of an individual unit) will increase. However for many ecosystem services, increasing demand for (e.g. growing population) or increasing scarcity of (e.g. loss of wetlands) will only increase the marginal value up to a certain point. Beyond this threshold, as the area of wetland decreases or becomes more fragmented, or the local population increases, there is a dramatic decline in the functional capability of wetlands and consequently the amount or quality of services that are provided.

Adapted from Mitsch and Gosselink (2000).

The Hydrogeomorphic Principle of Ecosystem Services

Wetland values depend on the hydrogeomorphic location in which they occur. While many services are provided regardless of hydrogeomorphic location, other services such as flood damage prevention are only provided if a wetland is connected to a hydrologic network.

Adapted from Mitsch and Gosselink (2000).

The Substitution Paradox of Ecosystem Services

If different ecosystems are assigned different values in a given landscape, recommending the substitution of more valuable types for less valuable types would be a logical extension of economic analysis. However, many services related to wetlands are either imperfectly-substitutable or non-substitutable.

Beneficiaries of Ecosystem Services

Individuals (or groups of individuals, i.e. stakeholders) perceive, affect or benefit from different types of wetland ecosystem services. This may be related to their occupation and their daily interaction with a wetland and its services. Other factors that can affect an individual's perception of wetland values are income, culture, and education. This means that different stakeholders perceive different benefits from wetlands and as a consequence, will assign a different value to any, single service (if they were asked for a level of willingness-to-pay in a stated preference survey, for example).

-

Spatial disjunct: Depending on the type of service, the beneficiaries of ecosystem services may differ from and be distant from those who implement land use conversion and development (and subsequent loss of services)

- Temporal disjunct:Temporal benefits may accrue to later generations while monetary gains from land use conversion are immediate

Common types of stakeholders are:

-

Direct, extractive users harvest wetland plants, waterfowl, mammals, fish, and shellfish for food, fiber, or other economic purposes. They may also extract minerals, peat, or clay found in wetlands. In some cases harvests from a wetland may exceed its primary production, in which case the wetland system will have depleted stocks and may also lose resilience after disturbances.

-

Agricultural producers drain and convert wetlands to agricultural land, because, at least in the short term, the soil is fertile, nutrients are plentiful, and water is freely available.

-

Water consumers use wetlands for providing drinking water, agricultural irrigation, flow augmentation, etc.

-

Urban and rural developers convert wetlands to more developed (and more economically profitable) land use/ land cover types such as residences, commercial sites or transportation infrastructure. Much of this conversion is nearby expanding populations and economic activity where the demand for utilizing undeveloped land is high.

-

Indirect users benefit from indirect wetland services such as storm abatement, flood mitigation and water purification that accrue to individuals and communities across large catchment areas; often without knowing what the wetlands are providing.

- "Nature lovers" and recreation users want to conserve wetlands because of their scenic beauty, open space, biological diversity or on-site recreation opportunities such as bird watching.