Oregon Explorer Top Menu

You are here

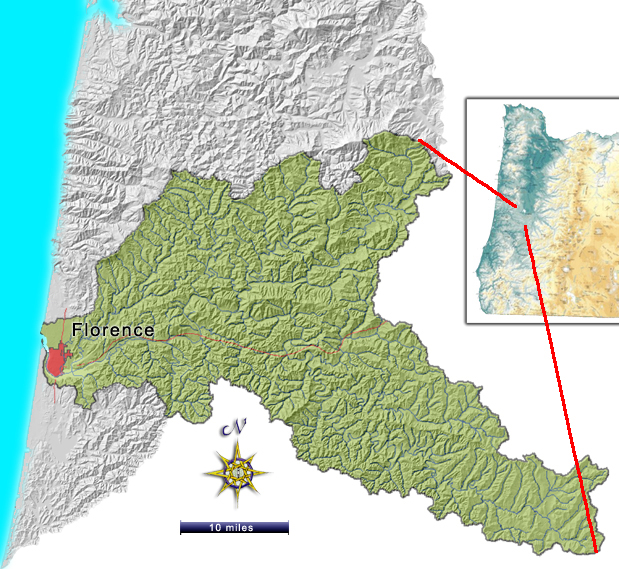

Siuslaw Watershed

Landscape

The 773 square mile (504,000 acre) Siuslaw (sei-YOO-slaw) River basin is located on the central Oregon Coast. It snakes from Lorane Valley and Low Pass in the east through the Coast Mountain Range to Florence and the Pacific Ocean in the west. "As-the-crow-flies" the distance is about 50 miles, but the river is nearly 120 miles long. Mountain ridges on the north and south separate the Siuslaw from the Alsea and Smith Rivers. Near the coast, low dunal hills separate the Siuslaw from several small, self-contained lake basins. The east edge of the basin is separated from Willamette River tributaries by a north-northwest to southeast trending ridgeline.

History

Historically, the Siuslaw Basin was one of the most abundant anadromous fish producers in the Pacific Northwest. The combination of geology, climate, forest development, and lifeways of the Siuslaw Indians established and maintained a system where salmon and the people who depended on them flourished for many years. Archeological records indicate that salmon "arrived" in the basin in abundance about 3,000-4,000 years ago. The evidence is in midden sites that show the diet of the Native people shifted to salmon at about that time. This corresponds roughly to a general cooling of the climate, which likely established conditions more favorable to salmon, and allowed them to extend their range south.

The most reliable early estimate indicates that 900-2,100 Indians were present in the Basin at the first recorded contact with Euro-Americans. These numbers may have been unusually low due to diseases that preceded settlement. Nevertheless, the Siuslawans had an economy and social structure, similar to that of most Pacific tribes, which insured that enough salmon would reach spawning grounds each year to perpetuate an abundant population. They did harvest plants and cut trees, particularly the western red cedar. But their harvest style was to split planks for homes off of live trees. Whole tree harvest, primarily for canoes, was selective and rare. Their exploitation of the salmon and other resources proved to be sustainable over hundreds, and perhaps thousands of years.

It was along the Nestucca River that many of the early pioneers came on sea going steamers such as The Della, The Elmore, and The Gerald C. These steamers frequented the rivers, bays, and bars from San Francisco to Astoria. Other pioneers traveled over the mountains by rough trails crossing many rivers with no bridges. In 1882, a road from Grand Ronde to the Nestucca Valley was completed greatly improving travel. Early "vacationers" would brave the elements by buckboard and horseback coming from the Willamette Valley to enjoy the Pacific Ocean and the river. It was usually at least a two-day trek. Campgrounds and facilities soon sprang up to accommodate these travelers.

Early cannery records indicate that the Siuslaw was second only to the Columbia River in numbers of coho. The average coho numbers from 1889-1896 were 209,000 fish. This compares to an average of just over 3,000 in the years 1990-1995.

Today

There are three distinct geographic parts to the Basin. First, in the east the landforms and settlement patterns are similar to the Southern Willamette Valley. Low, rounded hills frame broad, nearly level valleys that historically had prairie vegetation, still evident when the camas (historically an Indian staple) is in bloom in early spring. Oak and pine edge the valleys, giving way to Douglas and grand fir on cool, north facing slopes. Riparian woodlands are characterized by Douglas and grand firs, black cottonwood, and Oregon ash trees. Farms are relatively large and diverse, with new wineries overlooking the landscape. Lorane Valley and Upper Lake Creek basin characterize this part of the watershed.

As one travels west, the valleys narrow, the hills become steep mountains, and the ridges are more knife-edged than rounded. This is the Coast Mountain Range, and it covers the great majority of the total land area of the basin. Farms hug narrow valley floors. Homes are clustered along stream junctions. Roads wind along with the creeks. The forest crowds open areas, but numerous clearcuts are a significant part of the landscape mosaic. Forests are for the most part fairly young, with "old growth" stands only occasionally seen. The pattern of logging in the eastern half of the Basin reflects the "checkerboard" land ownership, a long-lived echo from the Oregon and California Railroad land grant. In the western half, most of the uplands are within the Siuslaw National Forest, with scattered in-holdings of private, industrial forestland. The valley floors are mostly small farms and homesteads.

West of Mapleton, where State Highways 36 and 126 come together, the Siuslaw River becomes very wide, with a broad floodplain, numerous wetlands, and tidal islands. This is the estuary, which leads to the dunes along the coastal plain at Florence, the largest community in the watershed. Here the land is characterized by barren sand dunes interspersed with pine woodlands and deflation plain lakes or wetlands. The wind picks up, the air feels different, and most residents make their living off of retirement pensions or tourists rather than from the harvest of trees, crops, or fish.

The Siuslaw River and tributaries provide habitat for chinook, coho, and chum salmon, steelhead, and sea-run cutthroat trout.

In the 1990s, watershed restoration efforts began in earnest. Many unneeded roads have been closed or "storm-proofed". Timber companies have worked to stabilize roads and replace problem culverts. Some valley-bottom landowners, particularly in Deadwood Creek, have restored wetlands and replanted or fenced riparian areas. Overall, the Siuslaw Watershed Council has distributed an estimated 25,000 trees to private landowners for riparian planting, resulting in about 20 miles of new streamside trees. Parts of the estuary are planned to be restored to tidal wetlands. Florence has upgraded its sewage treatment plant, and is taking progressive steps at recharging its aquifer by directing stormwater into the ground. The Siuslaw Watershed Council is gradually building a "watershed community" that will ultimately improve stewardship from Lorane to Florence.

To learn more about the Siuslaw 4th field watershed, visit the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Surf Your Watershed website.

Sources

Ecotrust Project: Inforain. A Watershed Assessment for the Siuslaw Basin. Jan 2002. HTML document.